Unraveling the Complexities of Food Insecurity in Los Angeles County

In a world where the word “equity,” especially when associated with government programs, often raises eyebrows, the recent resolution passed by Los Angeles County to create an Office for Food Equity is no exception. For many, including myself, such terms invoke thoughts of the insurmountable socialism calculation problem described by Ludwig von Mises. This theory argues that a centralized body cannot accurately represent or address the diverse, subjective wants of a populace – a scenario often leading to unintended outcomes.

As Los Angeles County embarks on this ambitious journey, a critical eye is essential. The yet-to-be-formed Office for Food Equity is born out of good intentions, but will it navigate the complexities of food insecurity effectively, or will it fall into the familiar traps of bureaucratic decision-making?

This blog aims to peel back the layers of ‘food insecurity’ – a term often misunderstood and misrepresented. Through this exploration, I seek to illuminate the real meaning of food insecurity, contrasting it with popular perception. Furthermore, this post sets the stage for a broader discussion: What can individuals and communities do to genuinely enhance food security and self-sufficiency?

Embedded in this article are insightful videos and charts that not only complement the narrative but also provide a deeper, more tangible understanding of the issues at hand.

And to provoke a bit of self-reflection: Have you ever stopped to consider the cost of your daily bread? (But don’t eat bread, that stuff will kill you). The reality of food insecurity might be closer to home than you think.

Understanding ‘Food Insecurity’

At its core, the term ‘food insecurity’ serves as a proxy for different levels of wealth and well-being in society. It encompasses a spectrum: at one end are those who face actual hunger due to severe lack of resources; at a slightly higher economic tier are individuals who, while not starving, live with the constant worry of not having enough to eat. Thus, ‘food insecurity’ is a term that binds these two distinct groups into a single category.

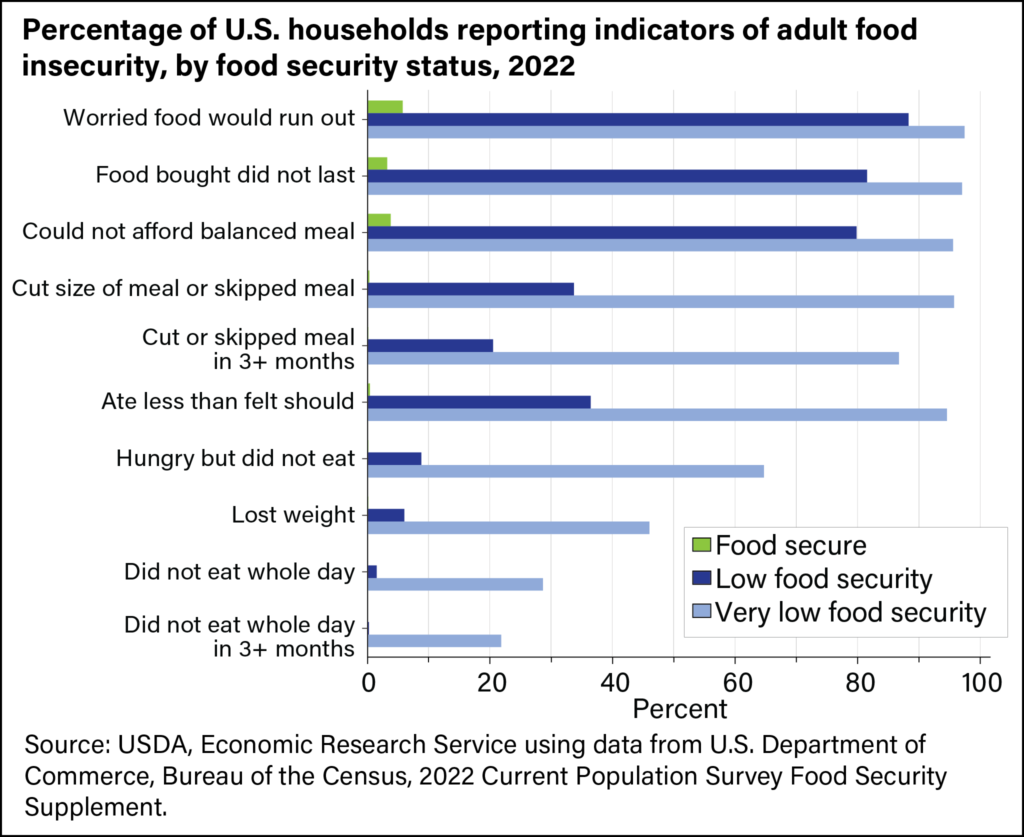

Breaking Down USDA’s Definitions

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) provides a nuanced understanding of food security, distinguishing it into different levels. These definitions are crucial in understanding the actual situation behind generalized statistics.

- High Food Security: Previously just labeled as ‘food security,’ this indicates no reported indications of food-access problems or limitations.

- Marginal Food Security: Still considered under the umbrella of ‘food security,’ this level hints at one or two reported indications, typically anxiety over food sufficiency or shortage of food in the house, but no significant changes in diets or food intake.

- Low Food Security: Formerly ‘food insecurity without hunger,’ it encompasses reduced quality, variety, or desirability of diet but little or no indication of reduced food intake.

- Very Low Food Security: Previously known as ‘food insecurity with hunger,’ this level involves reports of multiple indications of disrupted eating patterns and reduced food intake.

Interestingly, when examining the USDA’s data, a consistent ratio emerges: approximately 60% of those categorized as food insecure fall into the lower tier of concern, while 40% experience actual food shortages. This 60/40 split serves as a quick heuristic to gauge the severity of food insecurity in reported statistics.

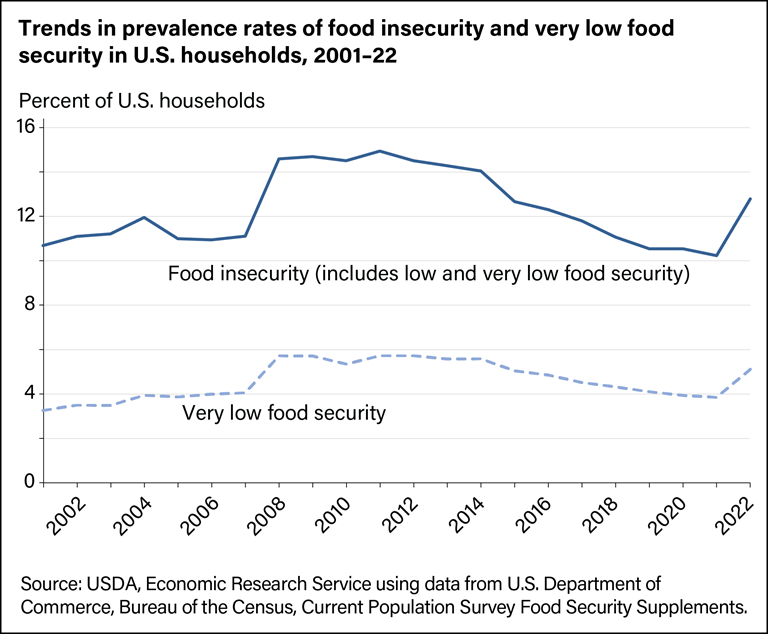

Public Perception vs Reality

When the media reports on ‘food insecurity,’ it’s vital to keep these definitions in mind. The general public often equates food insecurity with outright hunger, but as we’ve seen, the reality is more complex. This growing trend in media reports necessitates a deeper understanding of the term to avoid misconceptions and to grasp the true nature of the issue.

Key Takeaway

As ‘food insecurity’ becomes a more prominent topic in public discourse, it is imperative to discern between the layers of meaning embedded within this term. Recognizing the distinction between actual hunger and the fear of future food shortage is crucial in understanding the scope and scale of this issue. This awareness enables us to comprehend media coverage more critically and respond to the problem more effectively.

The Nature of Rights in Food Access

The concept of access to food as a right is a contentious and philosophically deep issue. From my perspective, rights are inherent properties of a human being, not something granted or bestowed. A right, in its truest sense, is an attribute of a normally functioning human being. It’s neither a privilege, which implies a granter, nor a granted entitlement. In the context of food access, this means that while food is a necessity for survival, it is not a ‘right’ in the philosophical sense. Access to food, like many other necessities of life, is bound by our individual capabilities, societal structures, and the resources available to us.

Negative vs Positive Rights

The debate often circles around the concepts of negative and positive rights. Negative rights, like those enshrined in the U.S. Constitution, are about non-interference – the right to be free from external restraint. Positive rights, on the other hand, suggest an entitlement to certain resources or services, such as food, healthcare, or education. However, the concept of positive rights poses a conundrum: if rights are intrinsic to human beings, how can they depend on the existence of others or societal structures? In a solitary situation, like being alone in a desert, the notion of a ‘right’ to food becomes meaningless without others to provide it. This underscores the philosophical stance that positive rights, while well-intentioned, are not ‘rights’ in the strictest sense but rather societal aspirations.

Government’s Role

In terms of government intervention, the most effective approach to ensuring maximal subjective satisfaction in food access might be for the government to minimize its interference. Regulations such as zoning laws, licensure requirements, and minimum wage laws can inadvertently raise barriers in the food industry, affecting affordability and availability. A freer market, less burdened by these regulations, could potentially lead to increased competition, reduced costs, and broader food accessibility. However, local governments like Los Angeles County are often constrained by state and federal regulations, limiting their scope for radical changes.

Historical Perspective

A poignant historical example can be found in the late Roman Republic, beginning with the Gracchi brothers’ initiative to sell cheap, subsidized bread. This well-meaning policy spiraled into a cycle of dependency, culminating in free bread, abandonment of rural farms, food shortages, and starvation. This historical lesson serves as a cautionary tale of the unintended consequences of government intervention in food markets.

Key Takeaway

The takeaway here is to understand the true nature of rights and the limitations of attempting to bridge the is/ought gap. Rights, as intrinsic properties of human beings, exist independent of societal constructs. While it is noble to aspire for every individual to have access to food, healthcare, and other necessities, labeling these aspirations as ‘rights’ muddles the philosophical understanding of what rights inherently are.

A Cautionary Perspective on LA County’s Food Equity Initiative

As we wrap up this exploration of Los Angeles County’s new Office for Food Equity, several key points stand out. Firstly, it’s vital to grasp the true nature of rights and understand the nuanced meaning of ‘food insecurity’ – which often differs significantly from the conventional image of ‘the hungry.’

Reflecting personally on the initiative, I harbor concerns about its potential effectiveness. While the intention behind creating such an office may be commendable, the approach could unintentionally exacerbate the issue it aims to solve. By intervening in the market, the government risks distorting supply and demand dynamics, potentially leading to increased food costs and deepening the very problem of food insecurity it seeks to alleviate.

The initiative might showcase visible successes, like distributing food to those in need. However, what remains unseen, borrowing from Bastiat, are the possible adverse effects: people who might have been on the brink of food insecurity being pushed further into it due to market interference. In essence, the solution may inadvertently contribute to the problem.

So, what can be done? The call to action here is clear: Take steps to increase your personal food security. Relying on government programs, no matter how well-intentioned, is not always the most effective route. In future discussions, we will delve into practical ways to enhance individual and community food resilience.

While government initiatives like the Office for Food Equity are born from a desire to help, it’s crucial to remember the broader implications of such interventions. As we’ve seen, the road to food equity is fraught with complexities and unintended consequences. As the saying goes, those who say they’re from the government and here to help might not always grasp the larger picture. Therefore, a cautious, well-informed approach is essential in navigating the intricate landscape of food security and societal welfare.

Additional Resources

- USDA Definitions: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-u-s/definitions-of-food-security/

- USDA Report: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/chart-gallery/gallery/chart-detail/?chartId=58378

- Zerohedge Article: https://www.zerohedge.com/personal-finance/los-angeles-county-approves-new-office-food-equity